Confronting the Cognitive Prison

He is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices…

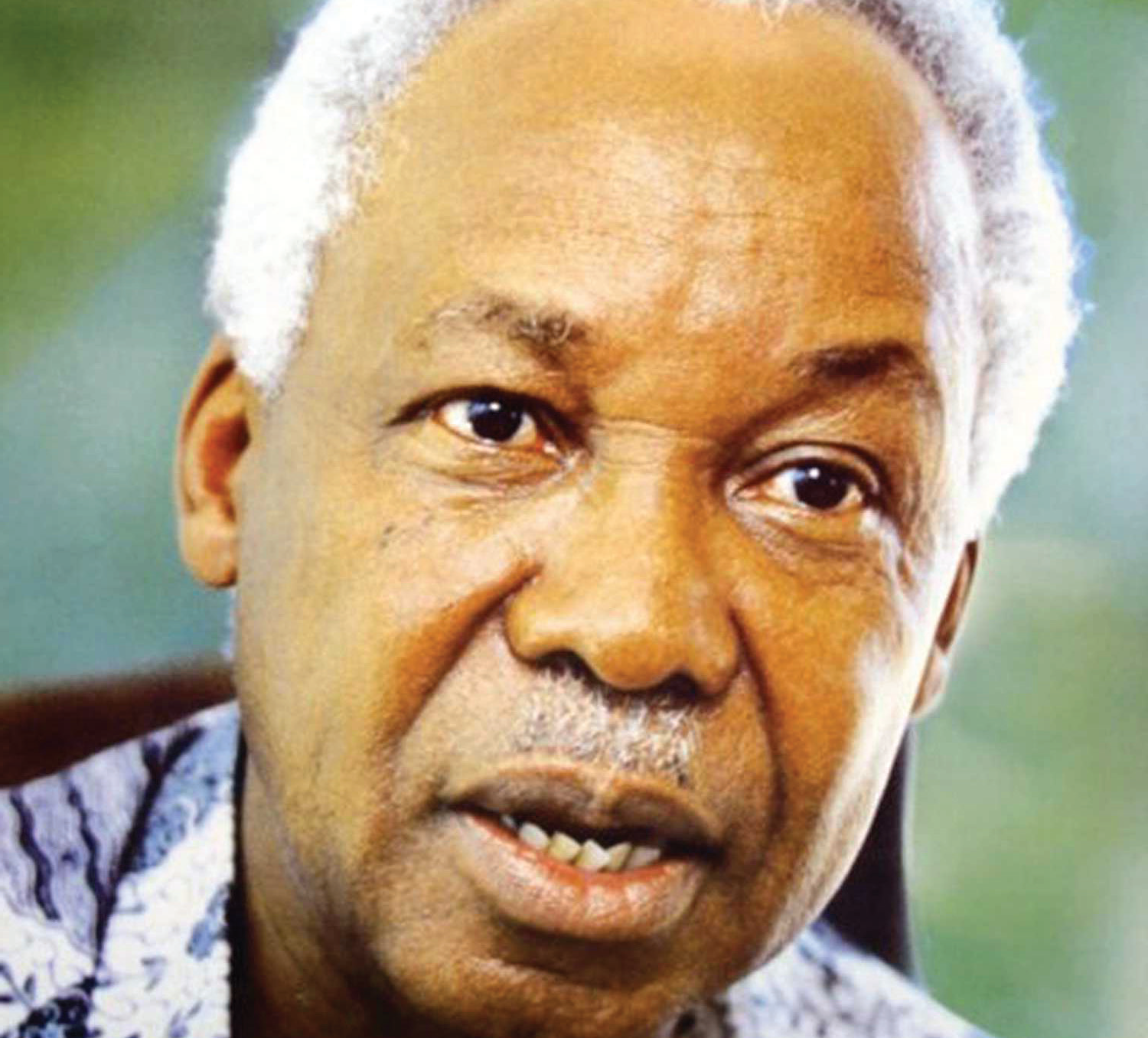

A CRITICAL REFLECTION ON JULIUS NYERERE’S POLITICAL THOUGHT

I begin this brief deliberation on the political thought of Mwalimu Julius Nyerere in a manner most unoriginal – by pointing a finger at the academic community in Africa at large. I want to shout out loud from the onset that we must come to terms with the inescapable violence that continues to characterise the political intercourse of Europe and Africa. I am certainly not the first writer to express this frustration and undoubtedly won’t be the last. Thinkers such as Nabudere, Anta Diop, Shivji, Ramose, Mutunga, Masolo, Bitek, Mudimbe and others have made similar pleas in the recent past that African scholars must pursue knowledge production that can renovate African culture, defend the African people’s dignity and civilisational achievements and contribute afresh to a new global agenda that can push us out of the political crisis of modernity as promoted by the European enlightenment.

Such knowledge, for instance, as demonstrated by Nyerere through Ujamaa, must be relevant to the current needs of the masses, which can then be used to bring about positive social transformation of our present plight.

As a new decade dawns, we are living in dangerous times. All over the world today, political leaders and citizens alike are developing thick skin by routinely rationalizing cruelty, exclusion and by engaging in habits that inculcate the systemic suppression of ‘others’. These are dangerous times because individuals are becoming smart and slick when it comes to disguising instances of dispossession, making it look normal. These are dangerous times because we are counting massive accumulation by a few as the solution to the massive dispossession of many especially here in Africa.

Across the waters in America, so bad is the situation that the respected American economist Paul Krugman has recently pondered in the New York Times whether the US could also be classified as a failed state. Professor Krugman points out that political scholars, who would normally study American democracy in splendid isolation, are now paying new attention to Africa and Latin America. They probably want to understand what happens when tyrants like Kagame, Museveni or Nkurunziza of Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi respectively ‘win’ elections and democracy morphs into something else.

In 2019 alone, the US is said to have withdrawn from several multilateral agreements and has recast itself to resemble the personality of its current president, a self-centered racist who appears to lack a trace of the idealistic internationalism that had been one component of US’s international character for more than a century.

As I write, impeachment proceedings have been formalized against the incumbent Republican president. Stimulated with the full glare of Trump’s political turmoil in America, countries in the oriental world are busy trying to reclaim their former prominence on the world stage. Unlike the situation in African academies, many Asian scholars are also engaged in an ardent effort to respond to the new reality by reexamining basic political principles. Their effort is not only academic or philosophical; it is also deeply moral – a situation where these scholars are making an effort at preserving what is of value in their own cultures and traditions while adapting to the changing geopolitical circumstances and engaging in new relationships. As Africans we must try and simply do the same.

In Africa today, there is a tragic contrast between intractable problems and knowledge explosion that has made politics an even more confusing business. The sheer quantity of knowledge available is mind-boggling and is increasing exponentially every day. And yet, in spite of this, most of our political problems are getting worse. There is, as such a need to transform the production and dissemination of knowledge to make it more useful for solving African problems.

Since gaining independence in the early 1960s, the African University and the African governments that created them have dismally failed to chart new paths for Africa’s emancipation and liberation and Africa finds itself in deep, multidimensional crises that require deeply thought out solutions and responses, if Africans are to reclaim what the late Koffi Anan once declared as ‘Africa century’. The problem for African academics is that we cannot just continue talking about the production of ‘knowledge for its own sake’ without interrogating its purpose. Eurocentric knowledge, as Edward Said once observed, was not produced just for its own sake. Its purpose throughout the ages has been to enable them to “know” us “the natives” in order to take control of our territories, including human and material resources for their benefit. To date, such control of knowledge continue being used to exploit African communities across the continent, most educational programmes at universities are designed and aimed at advancing the mental and geo-strategic interests of mainly leading Western countries and increasingly China as well.

Today, whereas Africa’s total external debt is estimated at USD 417 billion, around 20% of African government external debt is owed to China. Whilst a further 35% of African debt is held by multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, with 32% owed to private lenders, China remains the largest single creditor nation, with combined state and commercial loans estimated to have been USD 132 billion between 2006 and 2017. In a 2019 report by the World Bank, 18 African countries have been classified as at high risk of debt distress, a situation where debt-to-GDP ratios has surpassed 50%. Here in Kenya alone, the current public debt stands at a staggering USD 50 billion or 56.4% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Critics of the incumbent Jubilee administration led by Uhuru Kenyatta have pointed out that the government’s appetite for massive loans has been exacerbated by an equally pervasive culture of corruption in the country.

Indeed, Kenya has a history of multi-million-dollar scandals that have failed to result in high-profile convictions. Overall in Africa, a report by the Global Financial Integrity (GFI) estimates that Africa lost between USD 36 billion and USD 69 billion between 2005 and 2014 in illicit financial flows. This represents about 74% of all financing required (approximately USD 93 billion per year) to develop infrastructure to service Africa’s growth needs.

The African State as ‘Police Boots and Barbed Wires’

Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiongo captures well the current travesty in his 1986 classic ‘Decolonising the Mind’ where he called for further attention to the corrupting power of Western imperialism and the equally detrimental political and economic subservience of the African neo-colonial elites who are busy mortgaging African communities to the highest bidder – a situation that has led to a culture of what Thiongo calls “apemanship and parrotry enforced on a restive population through police boots, barbed wire, a gowned clergy and judiciary”. Needless to say, as presently constituted, the vast majority of Africans remain alienated from the postcolonial state which remains a colonial imposition and is incapable of expressing the basic ideals of the African community.

In my view as such, without apprehending the cultural, economic, and ideological aspects of European violence meted on African communities, it is impossible tofully answer the all-important political question, ‘what as members of African communities, are we trying to free ourselves from, and what are we trying to establish?’ The answer to this question, in part lies with the Tanzanian political philosopher whom until his sudden death in 1999, made significant strides towards the right direction.

Ujamaa Philosophy

Through Nyerere’s political thought, one sees Africans as trying to free themselves from European categories and the propensity to unwillingly embrace a Eurocentric worldview.

In other words, through his political lens captured in his Ujamaa philosophy, Africans are trying to recreate a historicity that has a philosophic practice that is both reflective and reflexive of their own lived political experience. Nyerere’s Ujamaa gave us a breadth of fresh air as far as political and development discourses are concerned. For so long now, theories of political and social development have been presented to African community as “scientific” theories extracted from their social and historical conditions implying that they represent the only valid paradigm that cannot be criticized or refuted. These theories have received such a widespread popularity that the United Nations has adopted them as its international blueprint for the so called developing countries mostly found in Africa. A critical and close reading of these theories reveals that they are nothing but a set of ideological premises that reflect the Western experience. One common characteristic of these theories is that they generalize their results to the entire world by eliminating their own specific characteristics and the historical conditions that underlie them.

It is for this reason that I argue that there is a serious problem with African academics sitting in high towers in Nairobi, Makerere, Lagos, Pretoria or other institutions of higher learning dotted across the continent, who unashamedly continue to perpetuate these theories whose net result has been to declare Africans as underdeveloped, irrational, stagnant, and reactionists.

Nyerere refuted this vehemently, arguing instead that despite of its spatio-temporal constraints, the Western model seeks to acquire a universal monopoly for itself and disregard other points of view especially those from Africans as parochial in spite of its own philosophical and historical limitations.

Cognitive Prison

This position has been supported by Indian philosopher Shiv Visvanathan who warns that Africa stands to pay a heavy price for failing to develop an organic intellectual infrastructure to adapt, translate and retool borrowed knowledge. He attributes Africa’s failures not only to the stubborn postures of current postcolonial governments or lack of resources in the continent, but to the failure by the academic and political fraternities to diagnose the problem of Africa’s development accurately owing to their failure to perceive the full depth and scope woven together by the confluence of the ideologies of science, law, politics, and development studies that are all pegged on advancing modernity which in the course of time, has managed to create a cognitive prison wall that has in turn sealed off academic institutions from real African communities.

By focusing on Nyerere’s political thought expressed in his Ujamaa philosophy, and in an attempt to address the question I’d raised earlier, ‘what as members of African communities, are we trying to free ourselves from, and what are we trying to establish?’ it becomes necessary to look broadly at the historical phenomena in which African achievements can be given proper recognition for without such recognition, it will be difficult for us, as Africans, to claim the 21st century.

African Epistemology

To begin with, I share Nyerere’s intuition that Political theorizing should be rooted in what makes sense to people and can guide them effectively in their public and private lives. As English philosopher John Dewey in his book The Public and Its Problems (1927) agreeably asserted, ideals are intelligible guides to action only when they extrapolate from the tendencies of existing practices and carry them to completion.

In the same vein, although I make no claim to provide an adequate account of the origin and development of Nyerere’s political thought and ideas, one thing that is certain is that he epitomized what Plato termed as a philosopher- king who combined great intellectual prowess with a healthy disdain for material wealth and ostentation; a man who could not be bought by money and who lived like what Tanzanian writer Jenerali Ulimwengu recently described as ‘a fakir when the lesser mortals of his age hid their philosophical emptiness and intellectual nakedness behind Rive Gauche suits and Hollywood villas’.

Nyerere, in effect thought as did German philosopher Martin Heidegger that being determines epistemology; epistemology does not determine being. In other words, Nyerere believed that what is, determines method, not the other way round. Indeedmany different cultures have developed many different knowledge systems, none of which has had any monopoly on knowing.

The notion that Africa is cast as an epistemological vacuum precisely because of the history of colonialism, coupled with the way the present paradigms of development and of knowledge are constructed, compels a rethink. With the exception of Afrikology as advanced by Professor Dani Nabudere, a systematic and theoretically adequate account of the relation of theory to practice, one capable of countering the hegemony of scienticism on all fronts, is still outstanding. However, meeting this need has been an abiding concern of Nyerere’s work expressed largely in his various publications: Freedom and Unity (1966), Freedom and Socialism (1967), Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism (1968), Freedom and Development (1973), Man and Development (1974), and Freedom, Non Alignment and South-South Co-operation (2011). From these books alone, one sees the growth and evolution of Nyerere’s philosophical understanding of Ujamaa.

His theory of Ujamaa was more concerned with practical political intent and in my view, it emerged from extended reflections on the nature of cognition, the structure of social inquiry, the normative basis of political, economic and social interactions of not only his Tanzanian compatriots but also of Africans in general. He saw social justice as an important element that could only be achieved by having human equality.

As such, the foundation of the Ujamaa philosophy is based on three principles: work by everyone and exploitation by none; fair sharing of resources which are produced by joint efforts; and equality and respect for human dignity. Nyerere’s belief in Ujamaa was largely driven by the fact that Africans are people who work together for the benefit of all community members. He as such stood firm against exploitation that he saw being perpetuated by the capitalist economic system as this encouraged individualism at the expense of the community.

He argued that capitalism fostered excessive individualism that promoted the competitive rather than the cooperative instinct in man. Nyerere’s Ujamaa advocated for unity among Africans. He envisaged Tanzanians and Africans from other part of the continent living together as a family – it is this aspect that gave principal meaning to his political philosophy. Ujamaa was as such aimed at restoring the cooperative spirit that African people had before their violent encounter with the colonial system.

Under the Ujamaa political system, Tanzania took strong and principled international stands. Tanzania was at the forefront of the Frontline African States which supported the liberation struggle against apartheid South Africa, white settler-ruled Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia), and Portuguese-ruled Mozambique and Angola. From early on, Tanzania also supported Congolese revolutionaries seeking to dislodge CIA-installed dictator Mobutu Seseseko. Tanzania welcomed Black revolutionaries from the world over, who debated various forms of Marxism and Pan-Africanism. One venue for these discussions was the Sixth Pan-African Congress, held in Dar es Salaam in 1974. Nyerere also took a strong stands against other African leaders and regimes like Idi Amin’s Uganda that were tyrannizing their fellow citizens. As I have argued in the recent past, to date Tanzania, thanks to Nyerere’s all-embracing vision, and justly so, continue to be portrayed as an African success story of state and nation- uilding, surrounded by nervy neighbours like Kenya whose 2008 post election violence left an indelible scar on its political conscious, or Uganda, South Sudan, and more recently Pierre Nkuruzinza’s Burundi, all of which have been ridden by conflicts and grave human rights violations. Worst still when compared to Rwanda, its immediate neighbour on the north west, whose 1994 genocidal orgy remains a scar on the world’s conscious and an acute reminder of how low humanity let alone ‘democracy’ can get.

Democracy

Nyerere understood democracy as a universal aspiration for popular self-rule and as a historically bounded form of governance that had to conform to traditional African structures. His attachment to democracy is instrumental for entirely pragmatic reasons. He saw it as effective in meeting the ineluctable circumstances of contemporary life: value, pluralism and conflict.

He however warned thatdemocratic institutions such asthose found across East Africa today were pegged on western democracy and that this will create a ‘crisis of modernity’ where communities will lose their cultural heritages and identities under the current wave of the so called ‘globality’.

Nyerere through Ujamaa urged that African communities and cultures must strive to improve upon their institutions and practices in order to remain relevant. Although he supported the idea of Africans borrowing ‘good practices’ from other cultures across the world, he argued that if not carefully approached Africans risked losing their momentum for cognitive growth since its various habits of thought and practice can become anachronistic if their ways of life are predominantly anachronistic. Nyerere saw an answer to this situation in community education.

It Take a Village to Raise a Child

Nyerere detested the Western education system, arguing that it was aimed at alienating Africans from their own value system whilst reinforcing Western values. This was in spite him being the first Tanzanian to study in Britain, securing his Master of Arts degree in Economics and History from Edinburg in 1952. He argued in 1968, that colonial education was not designed to prepare young Africans for the service of their own countries; it was instead motivated by a desire to inculcate the values of the colonial state.

His philosophical views on education were subsequently based on the notion that education was a lifelong learning process and a tool for liberation of man from the restraints and limitations of ignorance and dependency. He believed and advanced the adage that “It takes a village to raise a child”, which literally meant that the community was involved at every stage of one’s education. He was propagating for indigenous education, which he felt was well placed at preserving the cultural heritage of the African family, clan and society at large. This form of education, he argued, was aimed at everyone.

Nyerere, like the celebrated Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire, believed that the purpose of education was to liberate the ‘cognitively caged’ human being. Like Freire, he argued that education was a path to a permanent liberation and should make people self-reliant. In other words, education should help people to recognize their oppression and take part in their own community’s transformation. “People” Nyerere said, “could not be developed, they could only develop themselves”. A passionate advocate of the learner-centered approach for adult education, Nyerere believed that the teacher was only a guide for learning and not the dispenser of knowledge. Freire’s in his 1970 classic ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ reiterates the importance of the student-centric approach by arguing that through dialogue, the teacher ceases to exist – since the teacher is no longer merely the one who teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with students.

In Nyerere’s political thought, one can as such espouse new ideas such as constructivism, where learners are encouraged to use their own initiatives and autonomy, which in turn permits high level thinking to take place in a dialogue format open to questions based on one’s own experiences.

A brief journey through Nyerere political thought, invites stabbing questions about the role of universities in Africa especially at this day and age of the contradictory phenomena of globalization and the information society on the one hand, and clearly intensifying poverty, widening inequalities and the demand for social justice on the one other hand. This is in addition to our original question, “what, as African communities are we trying to establish?”

One thing certainly clear is that Nyerere’s philosophical texts serves as a major strategy for raising African consciousness and Undugu (brotherliness). His thinking is also a stringent discourse to the ravages of colonialism and its continuing forms of exploitation including current cognitive prisons.

Needless to say, African scholars need to take fresh stock of the full implication of their romances of and silences of knowledge transfer in the higher education sector in order to avoid paternalistic and blindness reproduction of knowledge for the sake of knowledge under the auspices of community development. We salute the elegant legacy of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere whose political life and philosophy continue to inspire in equal measure the young and the old throughout the world.

What's Your Reaction?

He is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices as well as the role indigenous knowledge systems play in the administration of justice in Africa. Educated at Stanmore, he read Politics at Middlesex for his undergraduate degree and Human Rights for his postgraduate at Bickbeck College. He holds two further postgraduate degrees in Ethics and in Public Administration from Nairobi. Wanda is very interested in how knowledge is generated and applied in relation to community development. His current research interests cover: Restorative democracy in Eastern Africa; Afrikology; Community Sites of Knowledge and Indigenous knowledge systems; Epistemology, Ethics and Culture. gahokenya@gmail.com