Afrikology and…

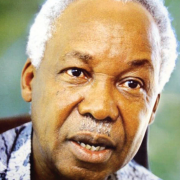

He is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices…

Contemporary Meanings of Race, Culture, and Justice in Post-Brexit Britain:

Where Can I Urinate?

This decade has begun with a growing air of frenetic activity that has engulfed Britain’s capital, London, triggered perhaps by the growth in volume and acceptability of xenophobic discourses on migration, and on foreign nationals including refugees in social and print media. Needless to say, British politics has for decades been infused with hostility to migrants, with both left and right governments pushing scapegoating narratives. The ructions in Westminster at the end of January 2020 when Britain finally exited the European Union took on historic proportions that saw the British pound fall as well as a rapid rise of death threats to ethnic minorities, all the while politicians have continued to quote poetry with a Powellian racial inflection. On the same note,and not to my surprise, while ethnic minorities make up 14% of Britain’s population, asizeable number of black people amounting to 73%in total, voted for Britain to remain in the EU, as did 67%of Asian voters. The figure was 53% of whites who voted in favor of Britain to leave the EU. Since the UK’s exit was finally approved by the EU in January, it’s safe to say that as far as race, culture and justice are concerned, things appear murkier than ever.

For me,the recent past has seen me more concerned with quarrels, battles, conflicts and at times controversies concerning African people in Africa and elsewhere in the diaspora. More specifically, I have found myself actively engaged in opposing those who attack Africans and attempt to belittle or deny the value and importance of Africans to humanity. In today’s Britain, under the aegis of Brexit, for instance, these attacks have come most frequently from those within the world of learning as well as the mass media corpus who uphold the misplaced claim that White is right and Black is wrong. These media clusters, appear to agree with one of Britain’s foremost cultural scholars Paul Gilroy’s hitherto hypothetical proposition that ‘race is an unhelpful fiction best set aside and kept out of respectable politics’.

Of late in British dailies, there has been an increase in the number of articles written mostly by senior political advisors and former policy makers that are calling for the re-colonisation of Africa all over again. Proponents of this view rightly appreciate that a new form of colonial domination is being instituted as part of a heavily militarized globalization process. However, they are wrong both when they fail to recognise that the ambiguities and defects of past colonial relations persist and when they fail to appreciate that those enduring consequences of empire aredirectly implicated in creating and amplifying many of the current societal problems succumbing Britain today.

Singing Myself Up

In this brief polemical note, using Afrikology’s conceptual lens, I want to try and Sing Myself Up as I engage the age old question of race and culture in relation to justice albeit in a post-Brexit environment which I find more representative of an emerging new form of racism.

My intention starts from a vantage point partially situated at home and partially thinking about contemporary representations of Blackness in London. London, need I say, as the capital of Britain is inhabited by a collection of culturally colourful characters – from gun runners to pill poppers; erotic dancers to exotic chancers; Yardies to bent coppers. However in the present context, London also represents a place where, according to Zambian scholar and UN’s special rapporteur Professor Tendayi Achiume, “structural racism is still an everyday reality for black people”. Considering that 44 % of London’s 8.6 million people come from an ethnic minority, this remains worrying, to say the least.

Professor Achiume pointed out further that “the environment leading up to the referendum, the environment during the referendum, and the environment after the referendum has made racial and ethnic minorities more vulnerable to racial discrimination and intolerance”. Achiume’s report noted that across the board, black workers in Britain earn far less than their white counterparts with the same qualifications – at every educational level. Another research by the Trades Union Congress (TUC), a confederation of unions in Britain,also revealed that there was a 23% pay gap between black and white workers. The harsh reality concerning such statistics on raceis that they contain echoes of the suggestion that Africans and other ethnic minorities are considered a form of planetary pollution in a place like London.

To counter this destructive

objective, Afrikology therefore calls for

the need for Africans to redefine their

world, which can enable them to

advance their self-understanding and

the world around them based on their

cosmologies.

Race and the Brexit Crunch

Subsequently, the recent hounding of the American Actress Meghan Markle as the former Duchess of Sussex together with her husband Prince Harry from the British royal family came as no surprise to most of us. Meghan’s decision to join the family that is the symbolic heart of the British Empire responsible for the troubled colonial past and the present post-colonial melancholyof a continent such as Africawas perplexing to many black people, as we wondered whether she fully appreciated the institution she had entered.

The former ‘royals’’ troubles aside, today in Britain, the continuing refusal to think about racism as something that structures the life of the post-Brexit crunch polity is associated with what has become known as a morbid fixation with the fluctuating substance of national culture and identity. For instance, the way in which British Police operate is still clouded with certain fixed expectations and stereotypes of the nature and location of ‘criminals’ and the manner in which they exercise discretion in making arrests or in deciding whether to prosecute, is often based on racist assumptions. A recent personal encounter serves as an illustration.

‘Where Can I urinate?’

A few years back, I was at a rundown part of north London, where someone, I suspect, must have told lies about a Kenyan man, for without reason he was arrested outside a supermarket not far from Edmonton Police Station. “You don’t seem to be taking this very seriously,” said the Inspector as we looked on. “I won’t say that I regard it as a joke”, the Kenyan man replied dismissively. “It must be a matter of unimportance because I cannot recall the slightest offence that might be charged against me,” he added. “We are mere servants of the law” the Inspector said, “so I can’t confirm if you are charged with an offence; only that you are under arrest. Proclaiming your innocence does not redound well upon you”. The crowd made up of mostly African and Asianimmigrants stared helplessly at the Inspector and his regiment as they dragged the poor man facing what seemed obviously an episodic inevitability.As I waited for my Enfield-bound bus alongside the crowd, I was approachedby a Ghanaian woman who asked what I thought at the time was a very strange question: “Where can I urinate?”…She was perhaps strained by the everyday horror she had just witnessed. Meanwhile, the Kenyan man’s “crimes” aside, having emerged from the evils of British sponsored totalitarian and corrupt KANU regimesof the past to the current Chinese supported debt-intoxicated Jubilee administration in the East African state, the poor Kenyan immigrant discovers that Britain also offers no respect for culture, diversity or justice.

Why should these anxieties over post-Brexit Britain be the black man’s burden all over again?

One thing for certain though, is that the tensions that currently exist between the police and black communities are not a recentphenomenon. Indeed, since the 1950s, successive generations of black people in Britain have felt under-protected as victims and over-policed as suspects. Although it can be argued that the apparent over policing of black communities can be justified as a response to thedisproportionate involvement of black males in particular forms of criminality, what cannot be ignored is that racism, whether institutional or that of individual officers, has played a central role in shaping the relationship that black people have with the British police.Ironically, according to latest figures published by the British police itself, hate and religious crimes rose 41%after Britain voted to leave the EU. A national poll carried out in 2019 found that in the seven months following the Brexit vote, over a third of black, Asian or minority people in Britain had witnessed or experienced racial abuse.

Post-colonial Melancholia

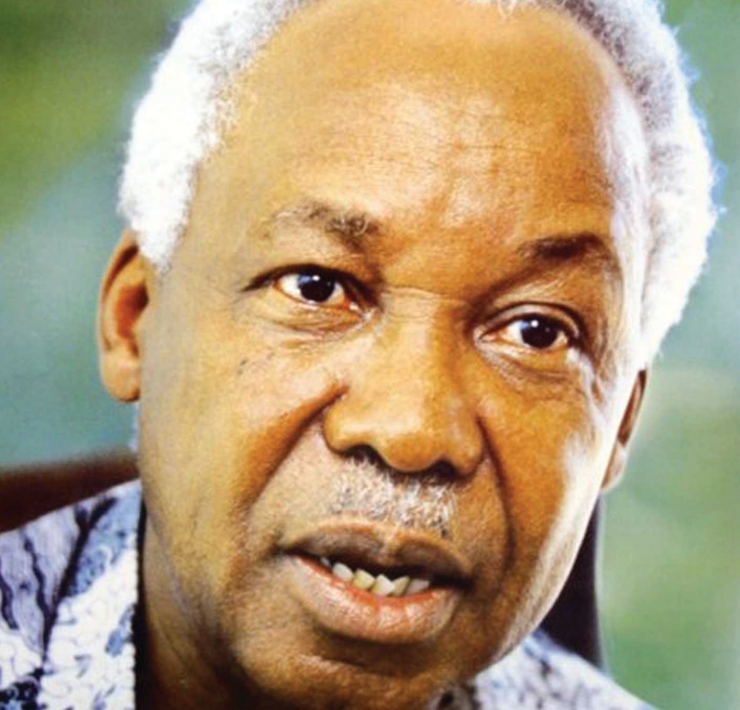

Over the years, some of us who have advocated for the idea that there ought to be a political or ethical obligation for Britain to deal with racism and its consequences have been dismissed by the establishment as endorsers of victimology, threatening Britain’s universal and liberal standards of justice and governance. My argument was, and still is, that today’s socio-cultural and socio-political conflicts which characterize the relation between Africans and the British political and justice establishments are firmly rooted in Britain’s imperial and colonial histories. Though that history remains marginal and largely unacknowledged, surfacing only in the service of nostalgia and melancholia, it represents a store of unlikely connections and complex interpretative resources. This is because the imperial and colonial life continues to shape political life in a developed but no longer ‘great’ Britain. So that, in a way, when the inspector said to the Kenyan immigrant: “so I can’t confirm if you are charged with an offence; only that you are under arrest. Proclaiming your innocence does not redound well upon you”, he was speaking of a person like me and my encounter with the voices coming out of what Ngugi wa Thiongo baptised as ‘centres outside of Europe’.

Looking back, the British Empire violently captured and then laterleft Kenya and its other regional colonies poor and devastated.Arecent London School of Economics report has rightly noted that although Kenya’s current constitution of 2010 introduced so-called democracy, it was overlaid onto a set of administrative structures and doctrines which had developed since the imposition of Crown Colony rule of Kenya in 1920. During the colonial time, the resolute imperialist Winston Churchill is on record as having shamelessly declared that ‘every white man in Nairobi is a politician’, and for that reason, whatever their divergent views, he argued that thewhite settlers had a duty to transform Kenya into a haven for white farmers, paid for not by Britain but by indigenous Kenyans – and not simply in terms of cheap labor, but by taxation too. Churchill’s ideas later saw prime farming highlands to the north of Nairobi designated a whites-only territory and Kenyan natives were banned from growing coffee and cotton.

Afrikology and the Integrative Paradigm

The on-going post-Brexit transitional predicament obliges us to try and understand the currentpreoccupationsof race, culture and justice in the larger historical settings. Bearing in mind what Paul Gilroy once posited, that whatever the immediate institutional settings, the residues of imperial and colonial culture live on whatever ‘race’ is invoked. Race, or as Gilroy rather puts it, “the presence of supposedly alien peoples”, constitutes the visible link to a cultural pathology which reaches into the innermost ways in which British society operates today. Indeed for ages, arguments over racial divisions, over who is human enough to qualify for rights and recognition have impinged upon the formation of epistemological and ethical as well as historical and political categories. During the 20th century, these arguments became closely connected with the complex demands for justice and freedom made by Africans and other colonised people bent on changing their political status by seeking liberty from and equality with those who had colonised them.

In Afrikology we learn that the new account of alienation that is drawn from the experiences of Africans in Britain in a post-Brexit age, alienation exists when the self is deeply divided because the hostility of the dominant white group in society forces the self to see itself as loathsome, defective, or insignificant, and lacking the possibility of ever seeing itself in more positive terms. More fundamentally, through the epistemic explanation of Afrikology, one sees clearly that the root idea of the post-Brexit raciology is aimed at forcing Africans and other elements representative of Blackness in London to survive in an atmosphere of outright hostility and in which they are not respected because of their racial origin. The hostility has a long term objective of causing the victims to become hostile towards themselves. In other words, the objective is to reduce the African immigrant to something “other” than them “self,” or the so called masters.

To counter this destructive objective, Afrikology therefore calls for the need for Africans to redefine their world, which can enable them to advance their self-understanding and the world around them based on their cosmologies. The process of re-awakening and recovery has to be one of a historical deconstruction, consciousness-raising and restatement not in the way others have argued, but by Africans tracing the origins and achievements of their civilisations with a view to developing new knowledge production based on African lived experiences in this global age.

Consciousness Raising and Self Understanding

Writer Gary Younge who wrote his last column on 10thJanuary 2020for The Guardian newspaper where he served as a staff writer for more than 26 years having done more to raise consciousness and understanding of everyday race, politics and culture in the UK. In his final article, he revealed that he was taking up a much deserved new assignment as professor of sociology at the University of Manchester. Over the years, the quality of Younge’s arguments in his column were comprehensive and convincing, they gave us all a healthy human understanding. In my view, the picture that emerged from his Guardian account is one of an integral, responsible and responsive human knower. As a counterweight to everyday prejudice in Britain, Younge’s students at Manchester are bound to benefit from him by learning first and foremost that all judgments especially of a racial nature require serious reflection.

In his insightful final article, he made an emotional tribute to his late mother, whom he described as having inspired his hawk-eyed political outlook reflected in his brilliant column forThe Guardian. Younge went on to sign off his column by describing the toxic Brexit situation in United Kingdom as a dispiriting time. “With racism, cynicism and intolerance on the rise, wages stagnant and faith that progressive change is possible declining even as resistance grows”.He argued that although things looked bleak and the propensity to despair appeared strong, it should not be indulged. For me, more importantly underlying Younge’s final word is the conjecture that individuals and human kind stands to flourish more humanely by their understanding of each other’s worlds. Younge seems to rightly suggest that by clearly seeing how others express themselves, and through responding by finding appropriate landmarks within ourselves, a greater self-understanding will be realized.But, having said that, the fundamental question for me still remains: why should these anxieties over post-Brexit Britain be the black man’s burden all over again?

What's Your Reaction?

He is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices as well as the role indigenous knowledge systems play in the administration of justice in Africa. Educated at Stanmore, he read Politics at Middlesex for his undergraduate degree and Human Rights for his postgraduate at Bickbeck College. He holds two further postgraduate degrees in Ethics and in Public Administration from Nairobi. Wanda is very interested in how knowledge is generated and applied in relation to community development. His current research interests cover: Restorative democracy in Eastern Africa; Afrikology; Community Sites of Knowledge and Indigenous knowledge systems; Epistemology, Ethics and Culture. gahokenya@gmail.com

In these confusing and troubled times, to rekindle the unrecognised (in both global northern and southern hemispheres of MOTHER-EARTH; the author has started a chapter on the ‘epistemological’ and ‘ontological’ bearing of AFRIKOLOGICAL CONSCIOUSNESS and PRAXIS. for the liberation of Afrika from finance-capital. Hopefully, there can be a dialogue between ‘indology’ and ‘afrikology’ that transgresses ideological alienation between the mental and manual labour.

Very inspiring,read more and prove a point to detractors who distorted African study centre mbale