Deepening Africa’s Economic Development

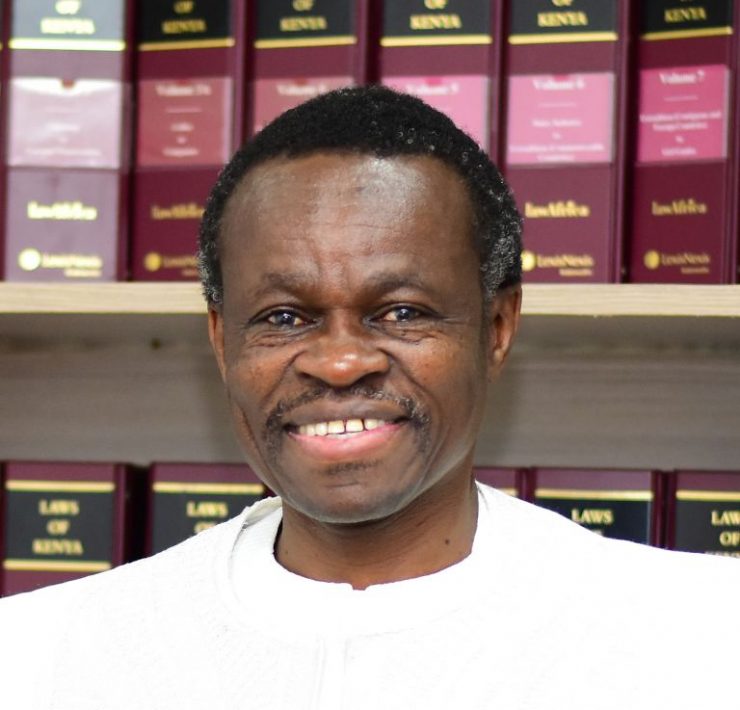

Dr. Bhengu is an Independent Researcher on Afrikan philosophy, Afrikology…

An African Perspective

East African Community Regional Conference:

Development, Growth and Power of the GDP: An African Philosophical Grounding.

Kampala, Uganda: 21 – 24 August 2014

Beating the West at its own game, argues Ashis Nandy (1983), is the preferred means of handling the feelings of selfhatred in the modernized nonWest, there is also the West constructed by the savage outsider who is neither willing to be a player nor a counter player’. The on-going struggle among Africans to overhaul and re-engineer the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) methodology, is a struggle to beat the West at its game. Unlike ‘the banditkings who robbed, maimed, killed and colonized’, and further, ‘faced and expected to face other civilizations with their versions of middle kingdoms and barbarians; the pure and the impure; the kafirs and the moshreks’ (Nandy, 1982, Hoppers, 2008), Africans are waging a sophisticated revolution, and this conference bears the testimony to that.

Nkrumah (1963 : xvi) was even more emphatic when he said that “Imperialism is still a most powerful force to be reckoned with in Africa. It controls our economies. It operates on a world-wide scale in combinations of many different kinds: economic, political, cultural, educational, military; and through intelligence and information services. It is creating client states, which it manipulates from the distance. It will distort and play upon, as it is already doing, the latent fears of burgeoning nationalism and independence. It will, as it is already doing, fan the fires of sectional interests, of personal greed and ambition among leaders and contesting aspirants to power”. Since imperialism still controls our economies in Africa, we are, therefore, challenged to confront it until it is defeated.

Economic Development Challenges in Africa

Whilst trapped within the colonial economic paradigm, Africa is slowly but surely making some strides in some certain services such as extending education, health, agriculture, politics, governance, democracy, etc., but the level of economic growth is still very minimal. The problem is how to sustain that minimal growth. There is a close relationship between policies that make growth more inclusive and policies that are likely to sustain growth.

Writing in The Thinker magazine, Vol.60/2014 – Quarter 2, Trevor Manuel (former South African Minister of Finance) argues that there have been steady improvements in the last twenty years. On the other hand the World Bank says the number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa living on less than $1,25 a day fell by about ten percentage points between 2001 and 2012. This small growth suggests that Africa is facing many challenges.

The extraction of minerals is not an end in itself, rather it is an important means to an end. This means a country has to be able to exploit its present comparative advantages to generate the resources to invest in new capabilities and skills to be able to move up the value chain. Secondly, African countries must be able to attract foreign investments into the natural resource sectors, but this must not translate into the exploitation of the African people, but it must improve the well-being of the people. African natural resources are not there to satisfy the needs of the foreign investors.

The 54 African countries in our continent need to consider the importance of integrated regional economies and encourage intra-African trade. As of today, many countries in a region export similar products and hence trade between countries on the continent is limited. As countries move up the value chain and diversify, there will be a more organic demand for trade across regions.

One of the challenges that Africa can and must construct is that of its Regional Economic Communities. In spite of their long existence through the Lagos Plan and the Abuja Treaty, with notable exceptions, these have not developed as was intended. The aim of all of this was designed to promote economic, social and cultural development, as well as African economic integration, as a means to increase self-sufficiency.

Intra-African Trade

Africa still accounts for a very small percentage of global trade. In terms of the trade share in global goods, it accounts for only 1,8% of imports and 3,6% of exports. The share of trade between African countries has declined from 22,4% in 1997 to around 12% in 2011 (African Centre for Economic Transformation. 2014 African Transformation Report: Growth with Depth). Whilst this decline can be attributed to the rapid increase of African trade with the rest of the world, argues Sinethemba Zonke (2014), African countries haven’t been able to take advantage of high growth rates by expanding with each other.

The level of intra-regional trade in Asia has played a substantial role in creating sustainable economic growth. Intra-regional trade has varied across Africa’s regional economic communities (REC’s), with trade blocks accounting for a greater percentage of continental trade. This highlights the important role RECs have played in bringing African markets closer together.

A common critique of Africa’s recent growth, argues Zonke, spurt is that it has been limited to a number of mineral and primary commodities which have been exported to regions outside the continent. Even within the category of primary and mineral commodities, African countries trade little with each other. This exposes an uncomfortable truth about Africa, in that its still stuck in the colonial mode, with its raw material only extracted to meet the needs of foreign markets.

The structure of African economies, with their reliance on primary commodities exports, has left the region extremely vulnerable to external global shocks. Africa’s growth in the past decade has been closely linked to China’s economic boom. With a slowdown in the Asian economy, demand for Africa’s commodities may begin tapering.

Presently Africa’s fractured into 51 diverse markets, argues Zonke, with populations of fewer than 10 million people. The gross domestic products of some of these national fall below the revenues of certain Fortune 500 companies.

Therefore, regional integration is imperative for expanding trade across the continent. By integrating, Africa would be able to unlock its full market potential.

An African Perspective of African Economic Development

Let us get the wisdom from our political forefathers, and this is what Nkrumah said in 1963: “Since our inception, we have raised as a cardinal policy, the total emancipation of Africa from colonialism in all its forms. To this we have added the objective of the political union of African states as the securest safeguard of our hard-won freedom and the soundest foundation for our individual, no less than our common, economic, social and cultural advancement”.

Nkrumah’s ‘Africa Must Unite’ remains a classic of its time, contains analyses of Africa’s position in the world economy., much of which would not look out of place today. It is either unity or poverty.

Five decades later, in spite of the development of several regional trading blocs on the continent, the dream of African economic unity and increasing strength within the world economy, seems a very long way away. Africa’s share of the world trade has declined over this period from 4% to 2% while the continent’s share of world GDP has also declined from 2,1% to 1,7%. These developments come at a time when not only is there increasing evidence that neo-colonialism has not been overcome but that neo-liberal economics has made a considerable contribution to keeping neo-colonialism alive. The challenge of African unity is also a challenge to the failed neo-liberal economics of the last three and a half decades.

The bulk of Africa’s exports are raw materials. Moreover, the hare of primary commodities in African exports is increasing: from 72 to 78% over the first eleven years of this century, argues Peter Lawrence in The Thinker magazine (Vol. 60/2014pg 36). Conversely, the share of manufacturing goods in total trade dropped from 21 to 16% while oil, the most important export, increased its share of trade value from 51 to 57% over the same period. While Europe and the US are still the main consumers its share of Africa’s export consumption from just under 5% in 2000 to almost 29% in 2011. Manufacturing as a proportion of GDP was only more than 15% in three countries, as compared with seven in 2000. Manufacturing was the key and this could start with the processing of the hitherto only exported raw materials. As Nkrumah noted: “In a country whose output of cocoa is the largest in the world, there was not a single chocolate factory (1963, 26-27)

Even now Ghana processes very little of its cocoa output with a small market and the dominance of the major multinationals in the global market.

It is by now a truism that decolonization meant for African countries that they became politically independent but remained economically dependent on their former colonizers.

The East African Community of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda attempted such a path with an industrial strategy that aimed to distribute industrial projects throughout the community. However, the context in which this kind of intra-African cooperation was taking place was in a world structured North-South rather than South-South, which is to say that the international corporations which supplied the industrial physical capital had their own strategies.

The population of liberated continental Africa is now around one billion and in real terms, that is, taking inflation into account, there has been little change in real continental GDP and a substantial decline in per capita income, given the more than threefold increase in population. The EU population is over 500 million with a GDP per capita of $33, 000 and a total GDP 13 times greater than that of Africa, and the market is dominated by very few large corporates. On the basis of these calculations African integration and unity is just as an imperative

It is, therefore, very prudent for the Friedrick-Ebert Stiftung together with the EAC to call for a conference of this nature to begin to do something along the lines of seeking an alternative, inclusive and broad-based economic model, not for Africa only, but for the entire globe.

We are, therefore, here today, in Uganda, to search for an alternative GDP methodology.

The complexity of the current global economy has to do with certain fundamental disjunctures between economy, culture, and politics that we have only begun to theorize.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 legitimised the creeping European economic and political dominance in Africa and obstructed the normal historical thrust and continuity of African societies, whether in cultural developments, economic growth, or state-building. With an unquestioned belief in their own self-righteousness and the depravity of Africans, Europeans were determined to change indigenous institutions and behavior and thus saw themselves as agents of civilization. This meant that Africans had to be taught different values, goals, and modes of behavior. This was a deliberate destruction of African cultural values and customs. This was probably the greatest legacy Europeans left in Africa. The deliberate destruction of African cultural values resulted in the seperation of African culture and imposed-economics. European economism is embedded in European culture, whilst Africa economincs, since it was imposed on Africans, remains seperated from their culture (see Bhengu’s writings: Africa Institute for Cultural Economy, 2013 – 2014). Such a vaccuum definitely creates problems for Africans. Prof Herbert Vilakazi (2005), Karl Polanyi (1944), George Ayitteyi (2005) Adedeji (1982), Nkrumah (1963), Huntington (1966) elaborate more on this point.

As a result, Africans had to abandon a lot of their values, including their ways of doing trade and business, and they were forced to do trade and business in European-cultural ways, rather than in their own local African ways. This change created problems for African economy, since European values of doing business are not compatible to African values. Hence, people want to emancipate themselves not just from poverty and shrinking opportunities, but from governance systems that do not allow them meaningful voice and responsibility. This conference is about developing our own economic utopia for EAC.

For Africa to have a real economic emancipation, it has to have her own economic philosophy developed within an African idiom.

Aristotle argued that man was not an economic being but a social being. Man’s economy was, as a rule, submerged in social relations. Man’s approach was sociological. For him, community, self-sufficiency and justice were focal concepts.

Prof. Adebayo Adedeji, former Secretary for African Economic Community (AEC), argued that Africa continues to be in search of a development paradigm that would rid it of abject poverty, the bug of disease and the quagmire of ignorance after over four decades of such endeavours. In pursuit of that goal a series of theories and concepts of development have been advanced, and tried to no avail. Most of them have been grounded in Western political and development traditions that failed to take cognizance of Africa’s cultural and historical background.

Adedeji’s advocacy of holistic human development is based on the general concept that society can only develop with the mobilization of its people: hence Africa would need to set in motion a process that puts the individual at the very centre of a development effort that is both human and humane, without necessarily softening the discipline that goes with development and enhances the human personality.

Such a development process, argues Adedeji (1982), should not alienate the African from his society and culture but rather develop his self-confidence and identify his interest with those of his society, thereby strengthening his capacity. This is exactly what the modern economics do to an African, and the challenge for us all is how do we embed the modern economics into our African culture and society.

Huntington (1996) argued very directly that ‘for an African civilization to have universal power, it would have to have a strong African-oriented economic philosophy, rooted in an African idiom. We believe that Africa has a relatively strong universal power, but still economically weak’.

But the fundamental challenge we are faced with, firstly, is that we need to find out why is it that Africa is still economically weak? Secondly, if we want to achieve a ‘universal power’ we need to have a relevant consciousness. The question is: Do we have such a consciousness? Thirdly, has the time not come for Africa to have her own pan-African economic philosophy?. We need to deliberate on these questions until we come to a solution.

What I would like to emphasize is the fact that it is wrong for Western modern economy to separate economics from culture. In our African situation, it is highly advisable to embed the economy in an African culture.

We need to ask ourselves these questions:

Why is it that the Eurocentric capitalism has failed to thrive in an African setting? We would like to know how does the East African Community view this situation?

Why is it that it is only the Third World countries that have a dual economy syndrome? What is the situation in East African Community regarding dual economy syndrome? Is there a regional plan to address this?

This failure to reconcile indigenous economic relations with exogenous economic values has led to a situation of two economies, i.e. the First Economy and the Second Economy. Does East African Community experience this problem?. By First economy we mean the white man’s colonial economy, and by Second Economy we mean an African indigenous economy, as we find them in Spaza shops, taxis, etc.

The ascendancy of Western neo-liberal economics, simultaneously with colonialism, on the African continent, African ethics and economic relations were dislocated and put almost into non-existence. African countries and Africans in general, were forced to embrace Western capitalism holus bolus, and as such, a vacuum was created in the African economic system.

For me, this is a clash of two civilizations, and our challenge is to reconcile these two civilizations. Therefore, the constitutive rules of the Bretton Woods conference of 1944 have to be overhauled, including, the GDP methodology, but what is GDP?

The Bretton Woods Legacy & GDP

According to Lorenzo Fioramonti (2013) the GDP measures the value of goods and services produced every three months, and can be represented by the following formula:

GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + eXports – iMports.

Since the creation of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the 1930s and further reinforced in 1944, economists who are familiar with GDP methodology have emphasized that the GDP is a measure of economic activity, not economic well-being. It is a formula used to determine the size and scope of a country’s economy, created by adding together the total amount of money earned or spent on goods and services produced by citizens of the country.

The use of GDP globally as a measure of economic progress was further strengthened as a result of the Bretton Woods Conference held at New Hamshire, USA, in 1944, a response to the Second World War, since there was a great deal of economic instability in a number of countries caused by unstable currency exchange rates and discriminatory trade practices that discouraged international trade. In order to avoid a recurrence of such instability, leaders of the 44 allied nations who gathered in Bretton Woods, resolved to create a process for international co-operation on trade and currency exchange and to “speed economic progress everywhere, aid political stability and foster peace” and improving economic well-being.

The key outcomes, then, were the establishment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD—now part of the World Bank). The IMF was created as a forum for collaborative management of international monetary exchange and for stabilization of the exchange rates of countries’ currencies.

The World Bank was established to provide investment funds for infrastructure reconstruction and development in war-torn areas and less developed nations in areas such as Latin America. In theory, the governing structures of these institutions were supposed to provide an equal voice to all member countries. In practice, because of its political and economic strength following, the Second World War, the US dominated both institutions. As a result, the US dollar, economy, and economic policies became the de facto standards against which other countries were compared.

Therefore, over a long time of economic growth – measured by GDP – it has become the sine qua non for economic progress. Today GDP and economic growth in general is regularly referred to by leading economists, politicians, top-level decision-makers, and the media as though it represents overall progress.

Criticisms of the GDP and Need for Transformation

Every country, particularly, in Africa, has what is known as an “underground economy,” which is defined as transactions between two parties that are not reported to the government. In South Africa, this underground economy is referred to as the “Second Economy”. As the government has no real means of tracking these dealings, they are not included in the calculations, and this missing information is one of many limitations of GDP. In some areas of the world, the underground economy makes up a large part of the amount of gross domestic product that a country generates. Oftentimes, with the lack of information regarding a country’s underground economy, many places technically have a higher GDP than what is reported.

GDP doesn’t account for quality of goods: Consumers may buy cheap, low-quality, short-lived products repeatedly instead of buying more expensive, longer-lasting goods. Over time, consumers could spend more replacing cheap goods than they would have if they had bought higher-quality goods in the first place, and GDP would grow as a result of waste and inefficiency.

While the GDP can be a good indication of how well a country is doing financially, there are several limitations of the GDP. One of the most important limitation is that the number usually provided by the GDP does not take into account the citizens’ quality of life, or how producing the products and services that make up the GDP impacts on the environment, and, therefore, the resources, of the country. This number also does not factor in financial transactions that are not reported to the government, making the reported GDP often lower than what it is in reality.

The current GDP formula fails, for example, to measure life expectancy, infant and maternal mortality, education, literacy, public health, etc.

A high GDP does not necessarily indicate a sound economy, since GDP does not measure the long-term sustainability of visible growth. A country, for example, may have a very low savings rate and/or misdirected investments; and thus will show an artificially high GDP number. Then the question is: What’s the point of measuring growth if we can’t tell whether that growth is sustainable over the long or even medium term?

The current GDP measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile.”

There is a significant agreement that the GDP provides a distorted view of trends in economic performance.

The problem lies in the conventional assumption that GDP growth is equivalent to progress and national wellbeing. GDP does not measure standard of living or societal wellbeing, as an index of economic output. The GDP mainly measures a country’s economy and is used as a measure for economic growth patterns. It does not capture the societal value of government services, which contribute to societal welfare, as well as issues affecting the wellbeing of citizens such as air pollution, or leisure.

The Way Forward

The time has come that the GDP measurements are revised, transformed and made relevant to our African setting. We need a GDP that will look into the performance of both the First economy and the Second economy.

We need a GDP that will look into the informal economy. We need GDP measures that will measure economic activity and changes in community capital—natural, social, human, and even the extent to which development is using up the principle of community capital rather than living off its interest.

Right now, the GDP methodology works against the values of our African metaphysics and cosmology, particularly Ubuntu philosophy. It is divisive, in that it caters only for the ‘developed’ countries, but not for the under-developing countries. The GDP methodology right now is not inclusive and not collective, which means it is still informed by its Western perspective of individualism, as against African perspective of collectivism.

Therefore, to determine an alternative GDP methodology, that will take into account the African setting, requires a thorough research, where we would reconcile the two perspectives, and then come up with something new and unique – something that will be globally acceptable.

Africa would need to come up with her own GDP methodology strategy of measuring her own economy. An African-oriented GDP must be able to measure the underground economy. It must be able to measure our second economy. Without measuring the second economy, the current GDP methodology does not give us the true picture of our African economy.

Our African-oriented GDP methodology will have to talk to our African metaphysics, our norms and our values. It must clearly tell us, Africans, why the current economic model is not embedded in our peoples’ culture, so that we would know where exactly lies the problems of economic growth?. It must clearly tell us why do we have, in Africa, a dual economy syndrome – a phenomenon that is not found in developed countries?

Therefore, the time has come for the GDP measurement system to shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people ́s well-being, and we need this urgently. Measuring people’s well-being, will be the birth of another human future. A future based on inclusion, not exclusion; on reclaiming the commons, not their enclosure; on freely sharing the earth’s resources, not monopolizing and privatizing them.

Ubuntu Paradigm

With this new stream, argues Catherine Odora Hoppers (2008, Kelvin Conference Centre, University of Glasgow), there is a growing maturity of dialogue that is not the result of a paradigm shift, but is the shift itself. Thus, from the ignorance and depreciating ideology along with social theories that claimed ‘terra nullius’ as a convenient rationalization for colonization and ill treatment, there is a need for honest need for those knowledge systems themselves, not just the recognition that they exist. The knowledge paradigms of the future are beginning by reaching out to those excluded, epistemologically disenfranchised, to move together towards a new synthesis, that recognizes the existence of indigenous knowledge systems.

In this synthesis, ‘empowerment’, which is usually more about resuming power (because power is never voluntarily relinquished), it is recognized that shifting of power without a clear shift of paradigms of understanding that makes new propositions about the use of that power in a new dispensation leads to vicarious abuse of power by whoever is holding it – old or new. Our new synthesis must be anchored on Ubuntu/Maat (Asante, M.K., 1990; Ramose, M. B., 1996)

Africa and the world are slowly beginning to recognize the value and potential of Ubuntu, as the root of African philosophy and being. It is the wellspring that flows within African existence and epistemology in which the two aspects Ubu and Ntu constitute a wholeness and oneness. Thus Ubuntu expresses the oneness of a being human, and thus cannot be fragmented because it is continuous and always in motion.

As a creative being, umuntu (a human person) is a maker of his/her world, which constantly emerges and constantly changes. In his/her existence, umuntu is the creator of politics, religion, economics and law. Through these creative activities, umuntu gains experience, knowledge and a philosophy of life based on truth. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) phenomenon was created by a simply human being in the early 1930s in the United States of America (USA).

Therefore, Ubuntu guides the thinking and actions of Africans, and must therefore be found in their lived historical experiences and not from philosophical abstractions that have very little meaning in actual life. This is where African philosophy differs remarkably from Western philosophies.

Therefore in his existence and being, umuntu strives to create conditions for his/her existence with other beings for, as the Zulu proverb says: “umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu”, which literary means: “a person is a person through other persons.” This belief therefore prescribes Ubuntu as “being with others.” The Sotho people say ‘motho ke motho ka batho’. To achieve this togetherness, reconciliation with those “others” becomes a continuous necessity of being (Bhengu, 2006)

Ubuntu, unlike the GDP methodology, is inclusive in nature as it considers all members of the community (organisation) as one entity aiming at achieving one purpose. There have been assertions that the ultimate success of any organisation operating in an African environment is premised on this Ubuntu framework, and it is a widely accepted belief that it is high time that this concept be given a meaningful chance. It is within this context that the current GDP mechanism has to be overhauled and reengineered so that it could talk to our African settings.

Ubuntu Economic

Constitutive Rules

In our search for an inclusive economic model, as we are doing here in Uganda today, we need to remember that an African is not a rugged individual, but a person within a community.

Ubuntu, which is the art of being human, teaches us concepts such as: respect, trust, compassion, sharing, caring and, above all, how to promote the good of a community and all its members. This notion refers to the principle of communalism, or living collectively, with the objective to ensure that no one falls too far behind anyone else. Collectivism associated with harmony and cooperation means working for the benefit of the whole, based on a long-term vision, rather than the benefit of constantly changing individuals. Unlike capitalism, an economy of any given country must serve the people of that country equally. This means that the economy of the East African Community must benefit everybody: urban or rural; black and white. It means there must be one single economy, not a double economy. We can, then, pose a question: Does the present GDP methodology work within this context or within another context.

Ubuntu can positively contribute to the socio-economic development of our post-colonial Africa and even give her a competitive edge in the world markets. This should particularly be so within economic and business enterprises whereby the Western based techniques of economics alone have been and remain inadequate to overcome the performance challenges. Hence if such techniques are not strategically fused with the innovative African practices and processes anchored in Ubuntu value system, they would only help to achieve competitive parity as opposed to competitive advantage.

The following constitutive rules, can hardly be measured by the GDP, but an Ubuntu-inspired GDP can easily measure them, thus fulfilling what is lacking in the present GDP methodology – that of measuring the well being of a society, rather than economic activities alone:

An action is good if it preserves the totality, fullness and the harmonious life of a human person; but an action is bad if it has a more or less decided tendency to break into and narrow the totality and fullness of humanism (Ubuntu) and its content.

A restriction on individual’s economic activity places severe constraints on the economic welfare of the whole society. If the individual prospered, so too did his extended family and the community.

An individual could prosper so long as his pursuit of prosperity does not harm or conflict with the interests of the community. The society’s interests are paramount. Unless an individual’s pursuit of prosperity conflicted with society’s interests, the chief or king had no authority to interfere with it.

Securing of the maximum satisfaction of the constantly rising material and cultural requirements of the whole of society through the continuous expansion and perfection of Ubuntu and higher techniques;

Any maximum profit must be equal to a maximum satisfaction of the material and cultural requirements of society;

Any maximum profit must be equal to an unbroken expansion of production, and

Any maximum profit must be equal to an unbroken process of perfecting production on the basis of higher techniques.

Ubuntu Business Management Principles

The move to dilute the hegemonic dominant economic paradigm is on in a big way, and our African scholars have made a stride in developing Ubuntu-oriented business management principles that aim at effecting the ease with which to infuse Ubuntu into the present unsatisfactory economy:

The principle of morality, which believes that no institution can attain its highest potential without touching its moral base.

The principle of interdependence, which believes that the task of wealth creation in a world of want and poverty requires the collective co-operation of all the stakeholders in the enterprising community.

The principle of the spirit of man, which believes that a man is entitled to unconditional respect and dignity, and organizations must work in harmony with him in the spirit of service and harmony. Organisations that fail to do this, cease to exist.

The principle of totality, which believes that the essence of collective participation in the creation of enterprising communities in Africa is crucial, because the building of a world-class organisation requires everyone in the organisation.

Therefore, in developing the East African Community utopia, it would be advisable, as Huntington (1996) warns us, to place everything we are doing and thinking, within an African idiom, and Ubuntu serves that purpose fully. Remember that Africa is a civilization without a universal power, but for Africa to attain that level of being a universal power, among other universal powers, Africa needs to have its own African-oriented economic philosophy – inspired by its own African economic humanism. To achieve this, we need a solid consciousness similar to the one promoted by King Senzangakhona’s court poet, when he said:

O Menzi, scion of Jama,

A cord of destiny let us weave,

That to universes beyond the reach of spirit-forms

We may ascend.

What's Your Reaction?

Dr. Bhengu is an Independent Researcher on Afrikan philosophy, Afrikology and Egyptology. He is an established and experienced author, self-publisher and managing director of Phindela Publishing Group & Editor-in-Chief of INQABA Journal, a quarterly publication that specializes on Afrikology. He describes himself as an Afrikan of Nguni (Zulu) extraction, but then a global citizen. Black, but being in total fusion with the world, in sympathetic affinity with the Earth... “I am black not because of a curse, but because my skin has been able to capture all cosmic eluvia. I am truly a drop of the sun under the earth.” He says.