Return our Afrikan Arts

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of…

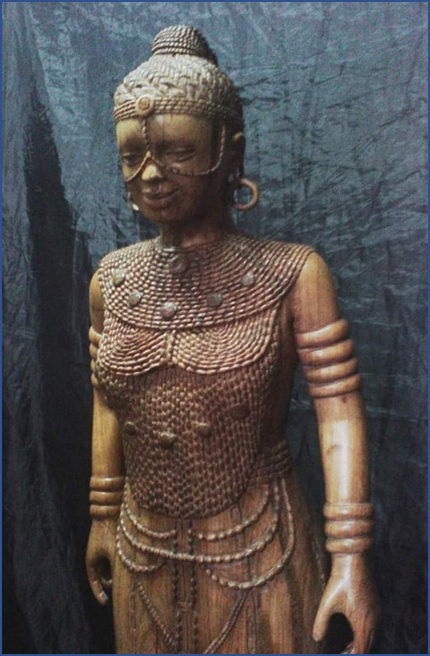

Media: Wood carving

Title: Colonial guard

Wait! Is it possible for anyone to lose the earth and heavens too? A hilarious chap in a single room placed a urinal pot next to his doorstep. While kicking his feet in the wee hours, the son of a man tiptoed in and stole the urinal pot. Early in the morning, we heard a loud cry of a stolen pot, and we then knew it was a bequeathed heritage from cucu (Grandmother). We were further scared that the urinal pot was a bath tap for a silver female python snake nicknamed”madame.”. Again, one time he traveled to his rural home to greet the cucu, and again the son of a man finally took his “kiki.” Now, if the son of man feels empathetic and brings back the urinal pot, it is referred to as a “return.” It is bringing something back to its original form or place. If the son of a man brings back his “kiki,” it will be called “reparation.” The dictionary calls it restoring, reinstating, or restitution. A learned friend will say it is unlawful possession of something taken without permission. It then applies to any African art taken during colonial and missionary expansion in Africa to extend illegal exports.

Media: Wood carving

Title: Colonial guard (rear)

Media: Wood carving

Title: African women

My auntie sobbed bitterly whenever she felt her singlehood family affairs were out of control. In her prayer, she would accuse my grandpa of witchcraft, primitiveness, evil, demons, paganism, and anti-Christ. Before thunder-lightening death struck my grandpa, he was a chief priest, a man of double personality, and a good sculptor in the villages. He sculpted African art such as masks, pots, house utilities, and abstract figurines. He was also an adulterous person, accused by the late Rev David Livingstone of touching women’s jujus whenever he performed a ceremonial rite in the village. One time, colonial guards arrested my grandpa for severe body cuts on his 100th-born daughter’s dimple. One night later, his cousin, working as a prison warden abetted his prison break upon surrendering all his wood carvings, which were then shipped to European museums.

Al Jazeera News reported that the current French leader was confronted by a hostile African crowd chanting and carrying placards that read in French, “ramène l’art!, voleur nous! voulons retrouver notre histoire!” (Bring back our art!, thief!; we want back our heritage!.) Dramatic men in dark spectacles and scowling faces reached out to the crowd leaders and grabbed their heads together like dumbbells. Al Jazeera’s reporter narrated how he saw crowd leaders falling apart like banana tucks while women wailed at the top of their sopranos’ voices. When French leader Emmanuel Macron reached another settled crowd in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, he gave a rebuttal speech on African art, heritage, and ethics. Africans in attendance were confounded with disbelief and shock that the French leader was well-schooled in the 1970 United Nations Economic, Social, and Cultural Organization Convention (UNESCO) and the 1995 International Institute for the Unification of Private Law Convention (UNIDROIT). Al Jazeera’s reporter quoted President Macron lamenting furiously, “O foolish Africans, who has bewitched you that you refused to enact legislation and abide by mutual agreement treaties in the joint International Council of Museums (ICOM)?”. Political analysts recognized that Macron’s powerful speech went a long way toward inspiring Namibians to celebrate the return of the Bible and the whip of Hendrik Witbooi. A story is told of how German colonial rulers amputated the Nama leader and roasted his head among the wild dogs. The whip of Hendrik Witbooi remains a symbol of Nama, the Namibian freedom fighter.

Many years ago, at United Nations (UN) headquarters, the late Zairian President, Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga Sese Seko Mobutu, broke out into hysterical laughter when the New York sheriff’s officers whisked him out of the United Nations Assembly. He had broken the podium into pieces and shouted for the return of the Tervuren collection to Zaire (the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The unprecedented behavior by Mobutu led the Congolese to enjoy Kongo artworks exhibited at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), the former Museum of the Belgian Congo. In another situation, the former Pan Africanists, the late Emperor Yohannes IV, Haile Selassie, and the Ethiopian Associations engaged in a shouting speech at the African Union (AU) headquarters in Addis Ababa. They accused the Mzungu (white man) of holding on to their Kush religion (early Ethiopian Christianity) artifacts. They also demanded access to the remaining Magdala treasure and ancient Kush manuscripts for Ethiopian churches. In another incident, the Federal Republic of Nigeria allied with the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the West African Museums Programme (WAMP), and the International Council of African Museums (AFRICOM) and pushed for the return of a few Obi treasures and Benin’s bronze from the Museums in the United Kingdom.

Since the time of African novelists such as the late Chinua Achebe and Henry Chavaka, Africans are still drumming their stories in many pockets of the world. I believe that until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero. African historians in higher education, such as the late Ali Al’amin Mazrui of Kenya, Théophile Obenga of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Sheikh Anta Diop of Senegal, dreamt of “African Cultural Renaissance is Preeminent,” a goal of the African Union (AU) Vision 2063. Five years ago, scholars at the African Studies Association of Africa Conference (ASAA) discussed topics on “Africa: The Past, the Present, and the Future” at a conference held at the United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya (USIU). Last year, Prof. Toyin Falola, a renowned African historian, gave a virtual keynote speech on Mwafrika (African) playing on the back of a crocodile, giving an explicit exposition on “Colonial Literature and the Future of African Art” at Kenyatta University. He challenged the Africans to come up with a strategic plan that would extend the storytelling of Africa beyond education curricula.

Sir Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann understood Ngugi wa Thiongo’s quote that culture, arts, and heritage can manipulate Africans’ self-definition and beliefs. These missionaries transversed the land of Africa, robbed Africans of their heritage, and injected the so-called “Salvation of Christ.” The consequence is that Africans are losing their inherited skills in crafts and indigenous knowledge in solving their own challenges. Globalization is making it worse with the rapid rise of fake bloggers masquerading as experts in African art. They are violently invading social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Google with misleading content on African art. My sincere sympathy goes to the current millennial generation because they are captives of social media deception and addiction. Their formative minds are being eroded regarding African culture, arts, and heritage. Even born-again government leaders are throwing out the towel with a baby against the influx of controversial content.

It is clear from The Parliament of Kenya: The Senate impeachment records that an African leader loves money, corrupt deals, and kickbacks. An African will sell his soul for a loaf of bread and take more than the owner’s plate. They will create political crises on the one hand and engage in illegal smuggling of African art on the other. It has been established that the high monetary value of African arts in the international market is a motivating factor for the illegal excavation and collection of heritage. For instance, during Moi’s era, a gluttonous museum official intentionally skipped the 1970 UNESCO code and illegally excavated Proconsul Africanus skeletons, an ape over fourteen million years old, and relics of Koitalel Arap Samoei. The man did not stop there; he facilitated the illegal export of excavations to the Natural History Museum in London. Currently, it has been observed that young African legislators lack competence in effectively debating matters concerning African art, among others.

Inclusion: I must say that the Mzungu is a clever man who still holds approximately 80% of African arts. When asked why, he says Africans refused to enforce the law and ratified the Convention’s recommendations. African nations such as the Federal Republic of Nigeria and Burkina Faso have tirelessly petitioned the United Kingdom and France to respect the 1970 UNESCO codes and the return of African art. Still, the Mzungu takes the Mwafirika around and around, arguing how the artworks were acquired, double ownership, and their fragile status. They are very good at arguments, citing legislation, and refereeing to mutual agreement treaties under the Joint International Council of Museums (ICOM). When the Mzungu was pushed to the corner, he released only 10% of the African art, which is now exhibited at local sites of the National Museum of Kenya and the House of Heritage, such as the Alan Donovan Murumbi Collection and Koitalel Arap Samoei Museum.

REFERENCES

Ogutu, W. (2023). The Future of Return of the African Artefacts: A Review of African Union (AU) Vision 2063 on Africa with a Strong Cultural Identity Common Heritage, Values and Ethics East African Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 6(2), 356-362. https://doi.or g/10.37284/eajass.6.2.1605 CHICAGO

What's Your Reaction?

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of Arts (Fine Arts) program at Kenyatta University. He is also a practicing visual artist specializing in drawing, painting, and sculpture within, Nairobi, Kenya. He focusing in Painting with its’ philosophy, education and extension to Africa contemporary Art. Most of his artworks focus on interaction, environment, and education. Wanyama has a passion for fine art research; its philosophy, development, and relevance. He writes on profound academic topics, where he has presented and published in international journals and conferences around the world. He is a consultant in innovation and creative strategy on issues affecting our society. He is currently a part-time teacher at some TVET institutes within Nairobi.

Quite elaborate

Thank you very much Naftal. Beautiful carvings you made.