Ancient African Reading and Writing Systems

Samuel Phillips is a writer, graphic designer, photographer, songwriter, singer…

DEBUNKING THE LIES THAT ANCIENT AFRICANS

WERE ILLITERATE BEFORE THE COMING OF

EUROPEANS

Inspired By the Article: 11 Ancient African writing systems that demolish the myth that black people were illiterate. Written by A Moore | Published on the Atlanta Black Star website

As an African, have you ever heard the statement that Africans were illiterate before Europeans came here? Or that there were no reading and writing systems before the arrival of the white man to the shores of Africa? I bet you might have heard that.

But here is the thing. There are lots of misconceptions about the African people which were deliberately created to push the narrative of backward and uncivilized Africans and which we, as African people, must begin to correct.

The importance of oral culture and tradition in Africa and the recent dominance of European languages through colonialism, among other factors, has led to the misconception that the languages of Africa either have no written form or have been put to writing only very recently.

So, the question is, were ancient Africans illiterate? Were there reading and writing systems in ancient Africa? Let’s find out in this video.

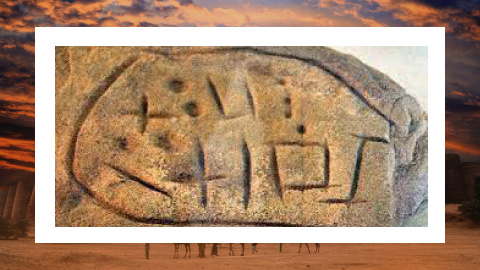

The Proto-Saharan (5000–3000 B.C.)

Dr. Clyde Winters, author of “The Ancient Black Civilizations of Asia,” wrote that before the rise of the Egyptians and Sumerians, there was a wonderful civilization in the fertile African Sahara, where people developed perhaps the world’s oldest known form of writing.

These inscriptions, of what some archaeologists and linguists have termed “proto-Saharan,” near the Kharga Oasis, west of what was considered Nubia, may date back to as early as 5000 B.C.

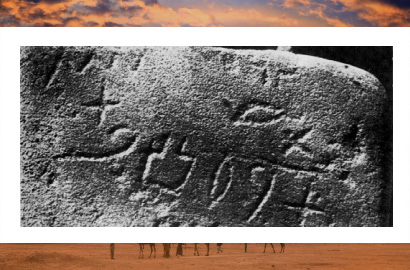

Wadi El-Hol or ‘Proto-Sinaitic’ (2000 B.C.–1400 B.C.)

In 1999, Yale University archaeologists identified an alphabetic script in Wadi El-Hol, a narrow valley between Waset (Thebes) and Abdu (Abydos) in southern Egypt. Dating to about 1900 B.C., the script bears a resemblance not only to the Egyptian hieroglyphs but also to the much older “proto-Saharan” writing system.

A similar inscription that dates to 1500 B.C. was found in Serabit el-Khadim on Africa’s Sinai Peninsula and has been deemed, by linguists, to be the basis for the so-called “proto-Canaanite” and Phoenician scripts.

This provides proof that Phoenician writing began on the African continent.

EGYPTIAN WRITING

Perhaps the most famous writing system of the African continent is the ancient Egyptian (Kemetic) hieroglyphs.

What many people do not know is that the Egyptians invented three scripts: hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic. These scripts were used by Egyptians for thousands of years.

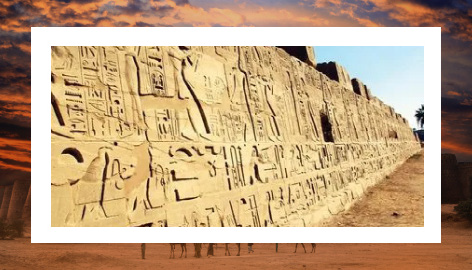

The Hieroglyphic (4000 B.C.–600 A.D.)

The ancient Egyptians called their hieroglyphic script “mdwt ntr” or “medu neter” (God’s words). The word “hieroglyph” comes from the Greek “hieros” (sacred) and “glypho” (inscriptions) and was first used by Clement of Alexandria (c. 200 A.D.) The hieroglyphic script was confined mainly to formal inscriptions on the walls of temples and tombs.

Hieratic (3200 B.C.–600 AD)

Ancient Egyptian hieratic writing was a simplified form of the hieroglyphics, used for day-to-day business, administrative and scientific documents throughout the dynastic history of both Kemet and Kush (3200 B.C.–600 A.D.). Some linguists have also shown similarities between hieratic and the alphabetic proto-Saharan writing.

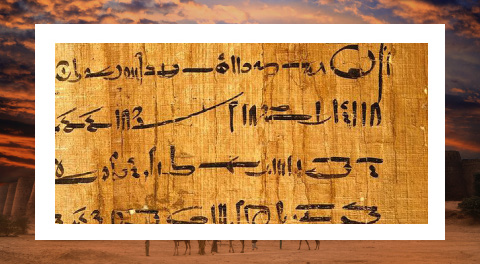

Demotic (650 B.C.–600 A.D.)

The term demotic was used by Greek writer-historian Herodotus (484–425 B.C.) to distinguish it from the hieratic script.

Whereas hieratic connotes “priestly,” the term demotic is derived from the Greek word demos, which means common people.

The demotic script is the only ancient Egyptian script that was used by just about every Egyptian. It is potentially the world’s first cursive or flowing script, and was mostly confined to pottery and papyri.

It is very important to note that demotic was introduced in Kemet’s 25th Dynasty, which had Nubian or Kushitic origins.

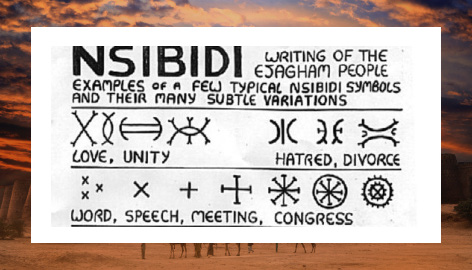

Nsibidi (5000 B.C.–present)

Nsibidi is an ancient script used to write various languages in West Central Africa. Most notably used by the Uguakima and Ejagham (Ekoi) people of Nigeria and Cameroon. Nsibidi is also used by the nearby Ebe, Efik, Ibibio, Igbo and Uyanga people.

The nsibidi set of symbols is independent of Roman, Latin or Arabic influence, and is believed by some scholars to date back to 5000 B.C., but the oldest archaeological evidence ever found (monoliths in Ikom, Nigeria) dates it to 2000 B.C.

Similar to the Kemetic medu neter, nsibidi is a system of standardized pictographs. In fact, both nsibidi and the Egyptian hieroglyphs share several of the same characters.

Nsibidi was divided into sacred and public versions, however, Western education and Christian indoctrination drastically reduced the number of nsibidi-literate people, leaving the secret society version as the last surviving form of the symbols.

Still, nsibidi was transported to Cuba and Haiti via the Atlantic slave trade, where the anaforuana and veve symbols derived from the West African script.

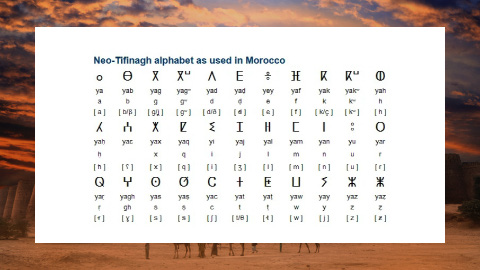

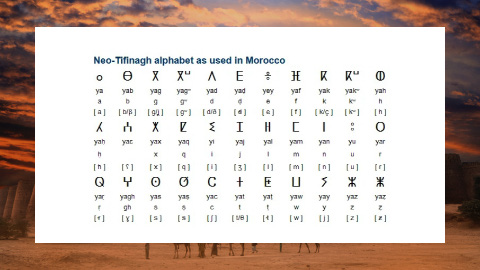

Tifinagh or ‘Lybico-Berber’ or ‘Mande’ (c. 3000 B.C.–present)

Rock paintings dating as far back as 3000 B.C. at Oued Mertoutek in southern Algeria show the earliest signs of a “Lybico-Berber” or early Tifinagh writing system.

The Amajegh a-Mazigh (Tuaregs), the Black people who mainly inhabit a vast area of North and West Africa, including present-day Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, southern Algeria and southern Libya, still use the Tifinagh script and are the only known group of Tamazight speakers who have used it continuously since antiquity.

However, the larger Tamazight-speaking community of the Sahara region has begun to adopt the Tifinagh script.

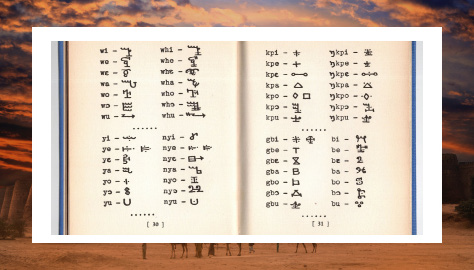

Vai (3000 B.C.–present)

Vai is one of the world’s oldest alphabetic scripts in continuous use, with more than 150,000 users in present-day Liberia and Sierra Leone.

It’s a highly advanced syllabary writing system with more than 210 distinct characters representing various consonants and vowel sounds used in the Vai language (a descendant of ancient Mande).

The popular story told about Vai is that it’s a wholly unique script invented circa 1830 by a West African whose friends helped him remember the writing system in a dream. However, evidence of its antiquity comes from inscriptions from Goundaka, Mali, that date to 3000 B.C.

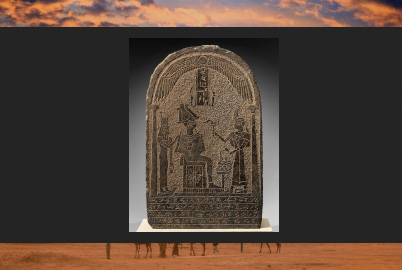

‘Meroitic’ or Napatan (800 B.C. to 600 A.D.)

The so-called “Meroitic” script was developed sometime around 800 B.C. in Napata, a city-state of Nubia in what today is northern Sudan. The script remained in use after the capital moved to Meroe until the 7th century A.D. Thus, some historians and linguists believe a more appropriate name for the script would be “Napatan,” in reference to the first known place of use.

Archaeologists have found countless inscriptions on stelae, temple walls and statues, and a few linguists have attempted to translate the text. It’s debated whether the Napatan script has been deciphered, but the current consensus is that the script is a wholly African language, with close similarities to modern languages of Taman (spoken in Darfur and Chad), Niyma (in northern Sudan) and Nubian (southern Egypt).

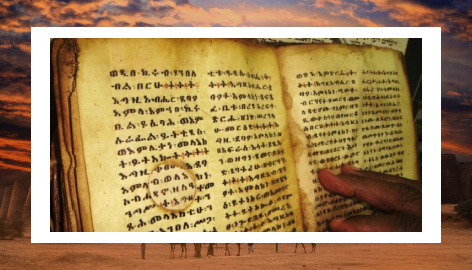

Ge’ez or ‘Ethiopic’ (800 B.C. to present day)

The Ge’ez script is an advanced syllabary script consisting of 231 characters used for writing in several Ethiopian languages. It is unquestionably one of the oldest writing systems in continuous use anywhere in the world.

Although the original Ge’ez language is only spoken in Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Tawahedo churches and the Beta Israel churches, the Ge’ez script is mainly used by speakers of Amharic, Tigre and Tigrinya, and many others.

The oldest-known evidence of Ge’ez writing can be found on the Hawulti stela, which dates to the pre-Aksumite era, or roughly 800 B.C.

‘Old Nubian’ (800 A.D.–1500 A.D.)

The so-called “Old Nubian” script is a descendant of both ancient Napatan and Coptic, and the Old Nubian tongue is an ancestor of the modern-day Nubian languages, such as Nobiin, Mahasi–Fadijja and Dongolawi.

It was used throughout the medieval Christian kingdom of Makuria and its satellite Nobadia. The language is preserved in at least 100 pages of documents, mostly of a religious nature.

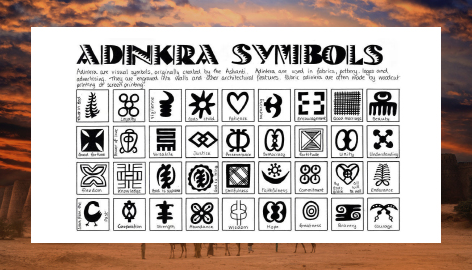

Adinkra

Adinkra symbols are visual symbols that originated in West Africa, specifically in the Kingdom of Ashanti in present-day Ghana. They are used in various contexts, including as decorative elements on cloth, pottery, and other objects, and as symbols of specific concepts or ideas. Each symbol has a specific meaning, and many of them are associated with specific proverbs or phrases. Some common Adinkra symbols include the “sankofa” symbol, which represents the importance of learning from the past, and the “gye nyame” symbol, which represents the supreme power and sovereignty of God. Adinkra symbols were originally created or designed by the Bono people of Gyaman, and are widely recognized and used throughout West Africa. They are often used as a way to communicate ideas and values in a visual way and are an important aspect of traditional Ashanti art and craft.

In conclusion, with all these ancient reading and writing systems that have been mentioned already, some of which are still in use to date, how could anyone say that Africans were illiterate before the Europeans came here? Like the Chinese who use their local writing system for their textbooks, science and everyday life, we need to start to give more attention to our ancient African reading and writing systems. It is very critical that we do so.

What's Your Reaction?

Samuel Phillips is a writer, graphic designer, photographer, songwriter, singer and a lover of God. As an Afrikan content creator, he is passionate about creating a better image and positive narrative about Afrika and Afrikans. He is a true Afrikan who believes that the true potential of Afrika and Afrikans can manifest through God and accurate collaborations between Afrikans. Afrika is the land of kings, emperors, original wisdom, ancient civilizations, great men and women and not some road-side-aid-begging poor third world continent that the world finds joy in undermining.