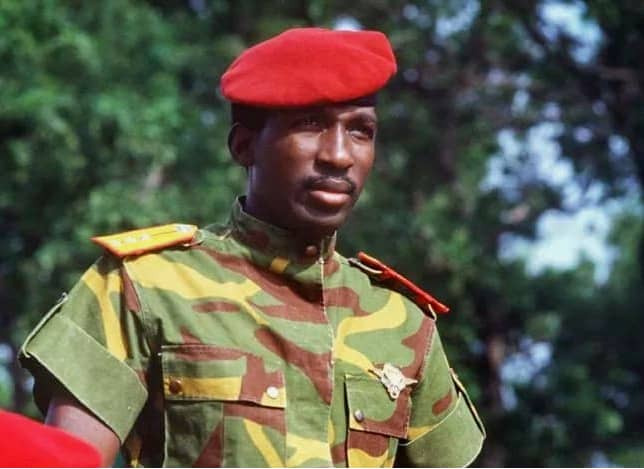

THOMAS SANKARA

Anselm Adodo is the Director of Africa Centre for Integral…

AND THE SEARCH FOR POLITICAL IDENTITY AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC LIBERATION OF AFRICA

Thomas Sankara, Military president of Burkina Faso, a small West African country, is often described as one of Africa’s lost heroes. A Marxist revolutionary, Pan-Africanist, anti-imperialist and a Feminist, Sankara made improvements in women’s status and liberation as part of his government’s central focus. For Sankara, liberation for the nation and the African continent is impossible without liberation for women.

As a demonstration of his conviction of women’s vital role in societal transformation, Sankara included an unprecedented number of women in his government, becoming the first African leader to appoint women into significant cabinet positions and recruiting them into the military. He banned forced marriages, polygamy, genital mutilation and all sorts of domestic violence against women. He dismantled the long-held belief that women should only work in the home by implementing policies that encouraged women to work outside the home. He made laws that permitted pregnant women to stay in school even when pregnant. In a deeply patriarchal society such as Burkina Faso, these initiatives were nothing short of a revolution, psychologically and politically.

One of Sankara’s most revolutionary initiatives was the introduction of the powerfully symbolic women solidarity day. On the Wednesday of every week, men took over all domestic work usually done by women: cooking, washing, cleaning and running errands in the market, to allow men to experience the enormous pressures women endure at home. Such a policy also aimed to correct the patriarchal belief that regarded household chores as inferior to office work. In his famous address to thousands of Burkinabe women on March 8, 1987, few months before his assassination, Sankara outlined his goal for women’s emancipation in Africa, which was to establish new social relations and unsettle the relations of authority between men and women and force each to rethink the Nature of both. Three years earlier, Sankara had changed the West African country’s name from the colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which means ‘Land of Upright people’.

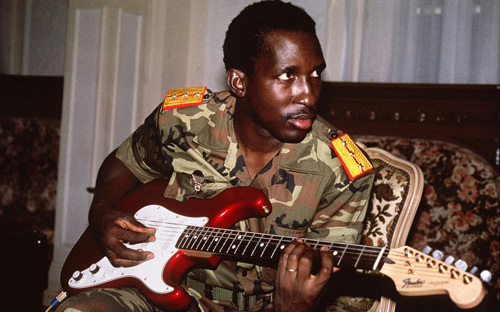

During his four-year reign as president, Sankara initiated one of the most ambitious and successful socio-economic policies ever undertaken by any African government. To set a personal example, he slashed his salary and that of his ministers and sold off the fleet of luxury cars he inherited from the president’s convoy, opting for the Renault brand, which was the cheapest available in the country. Sankara limited his possessions to a car, four bikes, a freezer and three guitars. He refused to use the air conditioning in his office since most of his fellow country people did not have access to the same. His salary was a paltry 450 dollars per month, and he forbade his portrait from being hung in public places. Sankara demonstrated that to be successful, a true revolution must have both subjective and objective, personal and official as well as emotional and rational characters to it.

His economic policy was INDE-genous rather than EXO-genous. In other words, Sankara promoted an inward-looking economic policy that uncovered, unveiled and activated the creative GENE or spirit of his society. His government declined all foreign aid, such as nationalizing all land and mineral wealth and gave a wide berth to neoliberal organizations such as the International Monetary fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Within three years, with no foreign support, an unprecedented 2.5 million children were vaccinated, and the infant mortality rate reduced from 280 deaths per 1000 births to 145 deaths per 1000 births. Not the ideal but a vast improvement from previous years. In the same period, Burkina Faso was becoming self-sufficient in food production, illiteracy levels vastly reduced and massive housing and infrastructural projects, such as the construction of over 700 kilometers of rail through local initiatives, without foreign aid, making Burkina Faso a model of Afro-centric economic transformation in Africa.

Like Steve Biko of South Africa, Sankara was murdered in his thirties, depriving Africa of one of her great revolutionary heroes. Even more unfortunate is the attempt of subsequent African leaders to bury the memory of Sankara, as his actions and legacy pose a direct challenge to today’s African leaders.

The uniqueness of Sankara’s Pan Africanism and liberation struggle lies in his Feminist orientation. Women’s liberation was at the forefront of his liberation struggle. That his best friend cut his reign short through a military coup will remain one of Africa’s great tragedies, and the conspiracy of silence from the Colonial superpowers, especially France, is a sad reflection of the hypocrisy and self-centeredness of western policies in Africa. That his policies could not be sustained after his death also shows that they were not well-grounded in local communities and not sufficiently institutionalized. Such policies, if they are to be sustainable, must be grounded in Nature, culture and community.

Quotes by Thomas Sankara:

“Debt is a cleverly managed reconquering of Afrika”

“He who feeds you, controls you”

“You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness.”

“Comrades, there is no true social revolution without the liberation of women.”

“The revolution and women’s liberation go together. We do not talk of women’s emancipation as an act of charity or out of a surge of human compassion. It is a basic necessity for the

revolution to triumph. Women hold up the other half of the sky.”

In fact, for the past 250 years, and most notably during the twentieth century, global politics and economics have been marked by two politically, economically, and intellectually divisive rather than culturally and psychologically integrative forces. This has been reflected in the “East/West” mutually antagonistic divide of communism/capitalism and the North/South chasm of wealth and poverty. The result, worldwide, has been, to a considerable degree, stasis and disintegration. The evidence is everywhere: climate change, terrorism, rising poverty, political tension, social chaos, and food insecurity.

The worlds of political economics and enterprise, on the one hand, and scientific research and learning on the other, are dominated, by one cultural frame of reference – “north-western” – to the point that the hidden strengths of other cultures, especially Africa, are being ignored by individuals, organizations, and societies, alike.

Marxism, Capitalism, Socialism, Communism, and any other political and social ‘ism’, while focusing on economics, technology and enterprise, failed to build their concepts on nature and culture, thus leading to unsustainable and imbalanced development. An integral approach, which takes account of the totality of the above, set within a particular African society, building up from Nature and community, and embracing culture, politics, economics, spirituality and enterprise, is a surer path to sustainable and integral development in Africa.

Such an integrated approach is what I refer to as Afrikology in my latest book. It is “Afri-” because it is inspired by ideas initially produced from the cradle of humankind located in Africa; it is “ko (logy)” because it is based on logos, the word from which the world was originated, but at the same time, an episteme, a worldly-wise eco-logical knowledge, and consciousness. It does not strive for superiority but reclamation and validation of its rightful position. It seeks to avoid any claim to an overarching epistemic superiority but stands for a plurality of epistemic directions: south, east, north, and west. Knowledge, therefore, is an interpretation that is always situated within a living communal tradition and our inescapable historicity. As illustrated in this research work, it is also co-created by individuals, communities, and enterprises naturally and communally, technologically, and economically, specifically out of Africa’s genius, alongside others.

Afrikology is born out of the interplay between its continent’s communities, their unique values and spirituality, and its multitudinous peoples’ reasoning and enterprise. Indeed, the rediscovery, in recent decades, by European and American social science, of emic anthropology, phenomenology, action research, semiotic economics and the range of ethno-methodologies can be traced back to an Afrikology of methodology. There are examples of such centres of Afrikological research-in-practice, through the work of ‘communiversities’, across Africa. Through Afrikology, we see beyond the superficial Western concerns of cancel culture and appropriation to dig deep into the soil of human society and unearth the African universe of solidarity and relationship: “Ubuntu: I am because we are”. It is a wild drumbeat that the world desperately needs to hear.

What's Your Reaction?

Anselm Adodo is the Director of Africa Centre for Integral Research and Development, Nigeria and founder of Arica's foremost herbal research Institute, the Pax Herbal Clinic and Research Laboratories (Paxherbals). His research interest is Phytomedicine, Taxonomy of African medicinal plants, indigenous knowledge systems, rural community development, Africanized economic models, health policy reform, and education transformation in Africa. Apart from publications in journals, magazines, national dailies and peer-reviewed journals, Anselm has written more than ten books. He is an adjunct visiting lecturer at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, an Adjunct Research Fellow of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, a Fellow of the Nigerian Society of Botanists, a Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and an adjunct professor at Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.